The economy is in an unusual situation. The normal fundamentals like jobs, wages, consumer spending, and business investment are strong, suggesting the economy is growing strongly. Yet there are growing calls that we’ll see a recession soon.

The economy is in an unusual situation. The normal fundamentals like jobs, wages, consumer spending, and business investment are strong, suggesting the economy is growing strongly. Yet there are growing calls that we’ll see a recession soon.

Why it matters: Those calls are coming because of persistently high inflation, which the Fed has started fighting with monetary policies that will reduce economic activity.

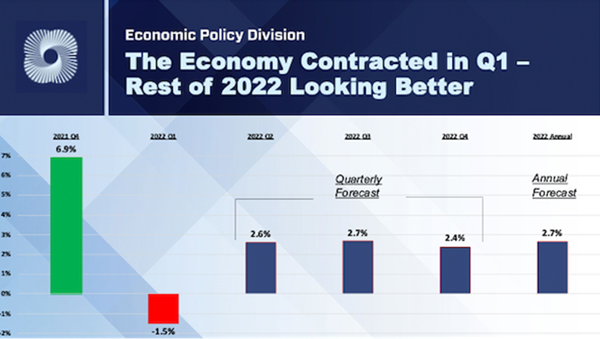

- Adding fuel to calls for a recession is the fact that the economy contracted by 1.5 percent in the 1st quarter.

Be smart: Swings in highly volatile components of GDP, namely our trade balance and inventories explained most of the contraction.

- The trade deficit increased by about $20 billion in March alone. However, in April, the trade deficit dropped by $20 billion, back to where it was earlier in the year.• Should this hold for May and June, trade will likely not be a drag for GDP in the 2nd quarter.

Looking ahead: A recession usually requires two consecutive quarters of contraction. We are anticipating 2.6% growth in this quarter and similar growth for the rest of the year.

Bottom line: Because the Fed is now fighting inflation, and because consumers may not be able to keep spending above inflation indefinitely, the risks of a recession a year or two from now are elevated. Our Chief Economists Committee put the risk at 30 percent to 50 percent, with most seeing it closer to the bottom of the end range.

• While this is higher than usual, it is not at a critical point yet.

COMBATTING INFLATION: WHAT’S BEHIND HIGH ENERGY PRICES AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT

By Matt Letourneau

Fill me in: In March, year-over-year consumer price increases topped 8.5%, causing the highest inflationary rise in 40 years. One of the biggest drivers has been skyrocketing energy costs, which impact virtually every sector of the economy.

While the war in Ukraine and supply chain impacts from Russian sanctions have exacerbated price pressures, energy prices were already escalating well before the conflict did. Gasoline prices have more than doubled since their pandemic lows and now average $4.21 per gallon nationwide. In the year preceding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, prices had increased by about 40% (over one dollar per gallon). Natural gas and electricity prices are important contributors as well. This can be clearly seen in the Global Energy Institute’s 2021 electricity price map, which registered a record 5.6% increase in electricity prices last year alone — a number that has only gone up in 2022.

What’s behind high energy prices?

- Supply and demand. Like other commodities, energy prices are dictated by basic supply and demand. As business and leisure travel have resumed and manufacturing has returned, demand has increased, but energy supplies remain constrained by a variety of factors.

- Uncertainty. The current Administration came into office with an agenda that includes phasing out of fossil fuels like oil and natural gas on an aggressive timeline. The exploration and production of oil and natural gas is extremely capital intensive and requires significant upfront investment and planning. Investors pay close attention to these kinds of signals, and fear of regulatory hurdles impacting returns have held investment back. Some politicians insist on blaming oil and natural gas companies for the current situation, accusing them of price gouging and putting forward debunked arguments about unused leases. That sends the wrong signal to the market. In part to balance this headwind, companies are now returning a higher percentage of the profits back to investors and investing less into new exploration and production.

- Supply chain and labor. Like every other sector, energy companies are still recovering from the pandemic-related lockdowns and are struggling to source the materials and workers necessary to expand production. Global shortages and transportation bottlenecks have pushed inputs like tubular steel and sand to historically high prices, and often aren’t available at all. This is limiting new exploration globally and preventing supply from keeping up with demand.

- Infrastructure. The United States lacks the necessary infrastructure to support enhanced production. Well-funded, coordinated campaigns have defeated major projects like oil and natural gas pipelines that are necessary to move products. New York and New England lack the pipeline capacity to take advantage of the nearby Marcellus Shale formation in Pennsylvania, and consequently have some of the highest energy prices in the nation. In fact, they are importing oil and natural gas from overseas—until recently, even from Russia. After years of bipartisan efforts to streamline permitting for badly needed projects culminating in reforms during the previous Administration, the Biden Administration has now moved to aggressively roll them back, sending us back to a 1970s era environmental review process that will slow down projects of all types—especially renewables.

- Lack of action. While the Biden Administration has expressed support for increased domestic production, their rhetoric has not been met with action. The Administration is seemingly still pausing some, if not all, new leasing and permitting on federal lands and waters (which made up 22% of oil production and 12% of natural gas). It has failed to put forward a new five-year plan for offshore oil and gas development even though the current one expires this summer. The lack of a new five-year leasing program will shut down new exploration and eventually hamper production in the resource-rich Gulf of Mexico. The situation onshore is much the same, with the Biden Administration failing to hold new lease sales to increase activity despite federal law clearly requiring them.

- Global markets. Oil, in particular, is a global commodity traded in a global market. Different types of oil products are produced in different places, depending on refinery configurations, and shipped across the globe. The price that consumers pay at the pump is reflective of the cost of crude oil, refining, transportation, distribution, and taxes.

The silver lining? When it comes to energy inflation, the United States does have one major advantage: it is the world’s largest oil and natural gas producer. This has helped to mute volatility in markets such as natural gas, especially relative to import-dependent Europe and Asia. For example, Europe now spends over 9% of its GDP on energy, the highest share since 1981 (the U.S. is at about 6%).

What should we do about it? Higher energy prices act as a tax on the economy and increase inflationary pressures throughout the supply chain. The Administration should therefore be clear and consistent in its support for expanded U.S. energy production, which will provide important signals to markets and help to limit the impact of energy on inflation. That includes holding comprehensive lease sales on federal lands and waters, moving swiftly to adopt a new National OCS Oil and Gas Leasing Program for offshore oil and gas development, avoiding imposing new regulatory burdens, and supporting the permitting reforms necessary to build energy infrastructure.

Bottom line: Addressing these issues won’t instantly increase supplies. Energy production takes a great deal of lead time. However, the current lack of support for energy production policies will ensure that it remains far below where it could be and will keep investment on the sidelines, making us more reliant on foreign sources and ensuring that higher prices are here to stay. That doesn’t bode well for economy-wide inflation.

Matt Letourneau is Managing Director of Communications and Media, U.S. Chamber Global Energy Institute, U.S. Chamber of Commerce.